Vi segnalo un originale articolo che illustra gli effetti della liberalizzazione economica degli anni novanta sul cinema popolare hindi, in particolare, ma anche sulla televisione e sulle campagne pubblicitarie. Il testo è molto lungo e ben dettagliato. Nel timore che in futuro potrebbe non essere più disponibile (è pubblicato da un sito tematico, dedicato alla liberalizzazione, collegato ad un istituto universitario), di seguito vi propongo qualche stralcio, ma vi suggerisco di leggere la versione integrale. “Maangta Hai Kya?”: How Hindi films saw liberalization, Uday Bhatia, agosto 2022:

'Badmaash Company (...) set in the 1990s (...) [i]s a surprisingly vivid illustration of the tectonic effects of liberalization in India. (...) As we see in Badmaash Company, the 1991 reforms and the ones that followed in their wake were dramatic enough to bring about visible and fairly rapid changes in people’s lives.

“Bollywood” today is used interchangeably with Hindi cinema. Yet the term did not exist until the mid-1990s. Before that, it might not have occurred to people in the industry to think of themselves as a professional ecosystem like Hollywood. The Bombay movie industry was a place where actors shot one film in the morning and another in the evening, where gangsters bankrolled features. (...) In 1998, the government fulfilled a long-sought demand and declared Hindi film an industry. This “industry status” allowed banks to advance loans for films, paving the way for corporate financing and professional studios and signaling the decline of private bankrollers with their attendant problems of black money and underworld pressure. Reduced tariffs lowered the costs of importing film stock, cameras, and tools for recording, editing, and mixing. Technological upgrades came in quick succession: Dolby sound, digital editing on Avid, sync sound, CGI. The industry turned a corner in 2001 with the release of Ashutosh Gowariker’s expansive Lagaan and Farhan Akhtar’s tasteful Dil Chahta Hai. Films looked and sounded different after that - and they weren’t watched the same way, either. The first multiplex, PVR, opened in 1997 in Saket, Delhi. Two and a half decades later, multiplexes have all but replaced single-screen theaters in metropolitan cities.

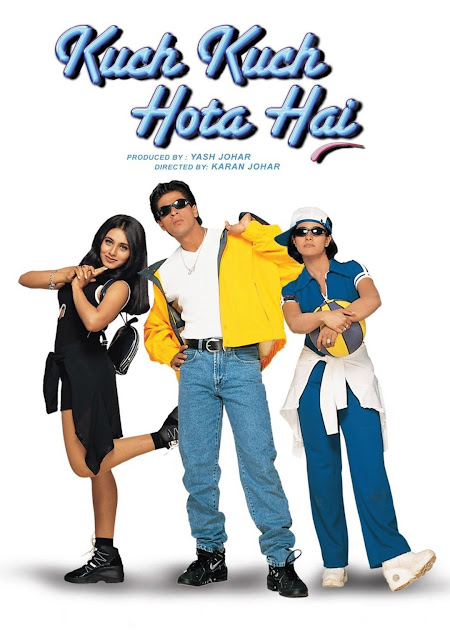

While these structural changes were taking place, cinema itself was changing. Much of this was tied to the visible and invisible effects of the liberalization process. Previously, conspicuous on-screen wealth had been a smoke screen for villainy or, at the very least, a corrupting influence. But from the 1990s onward, Hindi film protagonists were, increasingly, second- or third-generation rich kids. With Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994), Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Dil To Pagal Hai (1997), Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), Mohabbatein (2000), and Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham... (2001), there was a marked tonal shift toward youth, romance, and enough money to take money out of the equation. Producers discovered a lucrative overseas market that wanted to be told pretty, reassuring tales of home. If “Hindi film” was about the working-class hero and the mass audience, “Bollywood” stood for wealth and family values. (...)

If Sooraj Barjatya, Aditya and Yash Chopra, and Karan Johar were happy to show viewers the impossible dream, a few filmmakers explored how ordinary Indians were dealing with the changes around them. Ram Gopal Varma’s Rangeela (1995) is a particularly potent encapsulation of the post-liberalization moment. The playful argument of the musical number “Yaaro Sun Lo Zara”, in which Aamir Khan’s (...) Munna and Urmila Matondkar’s (...) Mili trade verses, is the new India of 1995 arguing with itself. “Gaadi bangla nahin na sahi na sahi / bank balance nahin na sahi na sahi” (If you don’t have a house and a car, that’s fine; / if you don’t have a bank balance, that’s fine), Munna sings. Mili responds with “Gaadi bangla agar ho toh kya baat hai / bank balance se rangeen din raat hai” (It’s amazing if you have a car and a house; / if you have a bank balance your life is made). (...) In another musical number that includes a magic carpet ride from Mumbai to New York, Mili (...) challenges Munna: “Maangta hai kya? Woh bolo!” (What do you desire? Say it!). (...)

The word maang - to ask, desire, or demand, depending on the passion with which it’s said - featured in another 1990s landmark. In 1998, Pepsi debuted an ad featuring Shah Rukh Khan, Rani Mukherjee, a young Shahid Kapoor, and Kajol, with the tagline “yeh dil maange more” (this heart wants more). Like so many other “Hinglish” phrases in those early days of cable, it became a rage, supplying the title of a film (2004’s Dil Maange More!!!, starring Kapoor) and the code word used by Captain Vikram Batra in the Kargil War of 1999. The 2021 biopic Shershaah brought it full circle by having Batra, played by Sidharth Malhotra, watch the Pepsi ad.

No actor personified the drive toward upward mobility better than Shah Rukh Khan. In Aziz (...) Mirza’s Yes Boss, Khan’s advertising man is hustling his way to success. “Jo bhi chahoon, woh main paoon... bas itna sa khwaab hai” (Whatever I desire, I attain it... that’s my little dream). At one point in the song, Khan is seen rolling in a sea of cash, an image of such frank materialist desire that it would have signaled moral decay had it appeared in any film made before the 1990s. (Satyajit Ray’s 1966 Bengali classic, Nayak, has a dream sequence with Uttar Kumar running through a field of cash; it quickly turns into a nightmare.) (...)

Liberalization changed Bollywood’s attitude toward money - and its villain profile. The move away from protectionism meant that dealers in contraband weren’t needed as they had been before. This led to the fading away of the smuggler, a staple villain (and sometimes antihero) from the 1940s to the early 1990s, as well as the black marketeer (though these figures still resurface, as in the influential Gangs of Wasseypur [2012]). The corrupt politician survived and adapted, as did the Hindi film gangster. The power-hungry industrialist and the manipulative seth turned increasingly benign; the hero or heroine’s father in 1990s rom-coms was often a businessman of some kind. Wealth was no longer a red flag. This laid the groundwork for the cartel-disrupting entrepreneurs of the following decade: Abhishek Bachchan playing a version of Dhirubhai Ambani, founder of Reliance, in Guru (2007), and the young upstarts of Rocket Singh Salesman of the Year (2009) and Band Baaja Baaraat (2010).

The luxury of choice (...)

The entry of cable TV in India was as big a jolt as anything liberalization wrought in those early years. Though small cable channels had started proliferating in the 1980s, most TV viewing was still limited to state broadcaster Doordarshan. Then, as part of the 1991 reforms, the government allowed private and foreign broadcasters to start operations. Star TV was one of the first to enter, bringing with it Hollywood movies and English-language soaps and sitcoms and music. It was a whole new world.

Music channels shook up Hindi film song and dance. The flash zooms, rapid cutting, and glossy production of videos on MTV and Channel V were adopted by younger directors, technicians, and choreographers such as Farah Khan, Ahmed Khan, and Shiamak Davar. Sophisticated recording equipment became available, allowing composers to improve on the muddy sounds of the 1980s. A. R. Rahman brought energy and eclecticism to film soundtracks: Roja (1992), Thiruda Thiruda (1993), and Bombay (1995) in Hindi dubs and, Rangeela onward, original Hindi soundtracks. A pop music industry sprang up and flourished for a decade or so before being swallowed by Hindi film.

This was the first generation of Indians who could watch foreign TV shows at home. Young people learned English from reruns of Friends and The Wonder Years. Indian TV channels sprang up - some in English, but most in local languages - and society reconfigured itself accordingly. (...) This was also the first generation of Hindi filmmakers who had to deal with audiences fed on a steady diet of foreign movies. It wasn’t as easy to steal from Spielberg and De Palma when their films were playing on TV all day. Viewers had more opportunities to compare local and international films, and to ask why they should settle for drastically lower production values. Luckily, Bollywood was in a position to do something about it. Import restrictions had eased and the necessary equipment could be brought in. Almost overnight, Hindi films became slick.

It was a time of relative innocence. (...) Yet many parents in those days did a lot of hand-wringing about the “Western values” their children were imbibing. (...) Bollywood gleefully incorporated the new values as well as the conservative correction. The scene that comes to mind most readily is Shah Rukh Khan, in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, somewhat cruelly leading a distraught Kajol to think that they were intimate the night before, then turning serious and saying he knows how important any Indian girl’s honor is to her. Later in the film, Khan keeps a daylong fast on Karva Chauth [festività hindu] along with Kajol: a spoonful of allyship to help the patriarchal tradition go down. In Yash Chopra’s Dil To Pagal Hai, Madhuri Dixit goes on a shopping spree in a gift store decked up for Valentine’s Day. She’s buying presents “to make myself happy” - retail therapy articulated simply and without guilt. (...)

This idea of a mixture - Indian and Western, traditional and new - was central to the early years of liberalization. After an initial run with foreign veejays speaking aspirational but difficult-to-understand accented English, Channel V and MTV started to air shows and promos in slangy Hinglish. Advertisers slipped a bit of English into their taglines. (...) Fusion music became a big deal. Colonial Cousins, a successful pop duo of the time, switched awkwardly between English and Hindi in its songs. A particularly ill-advised cross-culture stew was the version of “Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram” in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai - half-bhajan [genere di canto devozionale hindu], half-dance pop, all cringe.

Selling the dream

Post-liberalization, a “cinema of things” emerged: cars, clothes, accessories, TVs, gadgets, computers, décor, homes. Above all, there were phones ringing louder and louder across a decade in Hindi cinema. Early 1990s films found excuses to place characters in telephone booths - ubiquitous across India thanks to a government push - that had both dramatic potential and, with their cheerful yellow color, visual appeal. (Two of my favorites: Aamir Khan in Dil Hai Ke Manta Nahin [1991] showing off for the other reporters who don’t know he’s being scolded by his editor, and Shah Rukh Khan in Dil Se.. [1997] watching a charming village scene turn tragic as soldiers shoot an unarmed man.) Then, around 1996-1997, mobile phones started turning up in films. In Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya, an ambush is coordinated - and, at the last minute, called off - via cell phones. In Company (2002), Varma’s next gangster film, phones are wielded like guns. (...)

Bollywood was eager to participate in the new consumer economy - perhaps a bit too eager. Very quickly, the capitalist drive of the market and the promotional instincts of the film industry synced up. Brand placement for everything from cars to soaps started to appear in films. In Taal (1999), Subhash Ghai constructed a love scene around a Coke bottle. (...) Nothing was beneath a plug, no matter how prosaic the product. (...) The blatancy of all this in-film branding seemed to justify the reasoning that Bollywood wasn’t just another name for Hindi cinema but something altogether more business-like: films as products in a booming market.

As brands signed actors to be the face of their campaigns, advertising and film dovetailed until it was difficult to tell the difference. Ten minutes into Baazi (1995), Aamir Khan’s cop (...) shakes the Lehar soda bottle vigorously and sprays it on his face, the Lehar Pepsi branding on a crate taking up a quarter of the screen. (...) And audiences would have immediately connected Khan the actor to Khan the Pepsi brand ambassador. In 1993, he starred in the company’s first ad campaign in India, a sensational obstacle-course commercial with Mahima Chaudhry and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, which sparked a craze for the name Sanjana. (...) Multiplexes were often located in malls, so when you exited a film, the same movie stars you’d just seen on screen were now around you in the stores endorsing perfumes and sofas. (...)

Thirty years on (...)

The scaremongering about globalization changing the DNA of Hindi cinema is belatedly coming true in the streaming age. As taste flattens across the world, Bollywood is moving toward the global mean, with its eye on the success of Turkish dizi [serie] and Korean dramas. This means slowly tamping down the musical traditions that have defined it for over 80 years. Most films still have songs but with less dancing and lip-syncing, and there are not many directors left with a conception of Hindi film as a musical form. Even the lush romantic musical - the core of Bollywood - has seen a marked dip in the past decade. (...) Films about idle sons and daughters of rich parents became increasingly popular. (...) The occupational profile of Bollywood characters underwent a dramatic change. They were no longer doctors and lawyers and mid-level managers but rebellious entrepreneurs, photographers, architects, stand-up comics, video-game designers. (...) The working class receded from Hindi films altogether. It’s only in the non-Hindi cinemas that you’ll consistently find rural characters and the urban working class.

There has, however, been a return of the middle class. This new Middle Cinema began in the first decade of the millennium with the Delhi-set stories of Dibakar Banerjee and came to prominence over the next 10 years with the deceptively modest films of actors such as Ayushmann Khurrana, Rajkummar Rao, Pankaj Tripathi, and Bhumi Pednekar. These are life-size films, less exciting than the fantasies of the 1990s but more perceptive about the economic, familial, romantic, and interior lives of ordinary Indians. As the effects of liberalization spread outward from the urban areas, small-town settings for Hindi films have become increasingly common (though villages remain a rarity)'.