[Archivio]

La mostra New India Designscape era stata allestita dal 14 dicembre 2012 al 24 febbraio 2013 presso la Triennale Milano. Riporto di seguito il comunicato stampa:

'In mostra una inedita selezione dei più interessanti lavori dei designer indiani contemporanei, a cura di Simona Romano con la collaborazione di Avnish Mehta. New India Designscape presenta la complessità di un contesto, di un paesaggio, in cui prevalgono le interrelazioni e le continue interrogazioni sul progetto più che la fissità di identità nazionali e di figure in sé concluse, come i maestri delle generazioni passate. I giovani designer selezionati, permeati dalla matrice culturale dell’India ma fortemente contaminati da altri contesti, per lo più occidentali, attraverso i loro contributi progettuali propongono progetti che vivono in un delicato equilibrio tra l’innovazione e la tradizione.

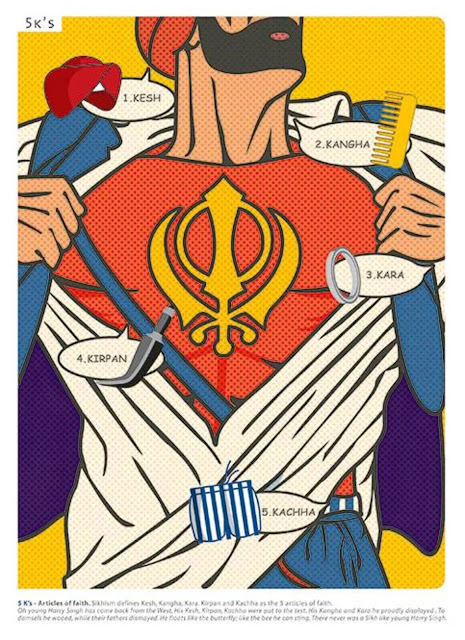

Spesso sono proprio i contenuti mitici a essere riproposti, con una certa ironia, in oggetti comuni (per esempio in Mr Prick di Sandip Paul, nei Lotus pieces di Sahil and Sartak, nella Cheerharan Toilet Paper di Divya Thakur, in Cut.ok.Paste di Mira Malhotra, nella Hanuman T-shirt di Lokesh Karekar, negli abiti di Manish Arora, nelle Varanasi Cows di Kangan Arora) a dimostrazione che l’antico e il contemporaneo, il sacro e il profano, si mischiano in un tutto non immediatamente decodificabile (per i non indiani) portando nel quotidiano contenuti profondi con risvolti, nell’era globale, quasi terapeutici.

Altri oggetti partono dalla cultura materiale autoctona (ardua sfida dal momento che gli oggetti più comuni e tradizionali dell’India hanno un coefficiente di modernità, funzionalità, ed estetica difficilmente superabile) o la reinterpretano innovando alcune tipologie (come nella Disposable Mug di Paul) o utilizzando alcuni oggetti comuni come dei semilavorati per crearne altri (la Choori Lamp di Sahil and Sartak, i lettering di Hanif Kureshi, i gioielli di Shilpa Chevan).

Negli oggetti in mostra vengono riproposti anche alcuni immaginari di un’India meno mediatica, che espone a un confronto tra diverse realtà sociali, a cui si guarda con un’accettazione, non rassegnazione, che prende forma, più o meno inconscia, in altri oggetti quasi surreali come il Bori Cycle Throne di Gunjan Gupta; e tra questi confronti non poteva mancare una riattualizzazione post-coloniale del rapporto India-Inghilterra (il lettering Englishes di Geetika Alok).

Le esigenze concrete della vita dei villaggi di cui è fatta la maggior parte dell’India non urbana ispira invece il cosiddetto barefoot design in cui una lavatrice a pedali (Reyma Josè) e la struttura in bamboo per il carico e il trasporto di pesi sulle spalle (Vikram Dinubhai Panchal), fanno la differenza in termini di qualità di una vita di per sé difficile. Ma il design si pone spesso in dialogo anche con le raffinatissime tecniche artigianali rurali per ridisegnare gli oggetti tradizionali (gli abiti di Aneeth Arora, il furniture design in bamboo di Sandeep Sangaru e Andrea Noronha, i progetti di Garima Aggarwal Roy, il Flying bird e le Singing Leaves di Rajiv Jassal, i Natural dishes di Sanders e Kandula, la Bambike, bicicletta in bamboo di Vijay Sharma) e incentivare le piccole economie locali (i Bamboo Cubes di M.P. Ranjan, i Chitku works di Priyanka Tolia).

|

| Bori Cycle Throne - Gunjan Gupta |

L’India urbana invece, quella tecnologica, che si caratterizza più per lo sviluppo di processi e semilavorati che per il design, quasi trova un alter ego artistico nei lavori di Padmaja Krishnan (Excess mobile e Wood Pc) e di Ranjit Makkuni (progettista di sofisticate installazioni interattive che ci connettono con il sacro).

L’India, anche nel design, si rivela così, difficilmente organizzabile, classificabile, sistematizzabile, decifrabile. Convivono progettisti che vi rimangono con l’intento di cambiare le cose (in mancanza delle aziende sono molte le produzioni self-made in piccole serie), che vi tornano dopo lunghi periodi di formazione e attività all’estero, o che lavorano lontano dalla grande madre senza mai dimenticarla nei loro progetti. Un paesaggio, il designscape indiano, ricco, che attraverso le diverse articolazioni del dialogo tra modernità e tradizione, potrà produrre nuovi contenuti per una società globale sempre in continuo divenire, e, proprio per questo, sempre alla ricerca delle proprie ancestrali radici'.

Vi segnalo l'intervista concessa da Simona Romano a Elena Sommariva, pubblicata da Domus il 15 febbraio 2013. New India Designscape:

'Sono molti i progetti in mostra sviluppati con le associazioni?

Simona Romano: La maggior parte dei prodotti raccolti qui è frutto di piccole autoproduzioni avviate dai designer stessi. In qualche caso, come lo sgabello-cubo di bambù di M.P. Ranjan, che combina lavorazione a macchina e dettagli artigianali di alta qualità, c'è anche l'idea di creare lavoro e dare vita a piccole economie. Le università stesse offrono corsi di barefoot design, che permettono agli studenti di trascorrere un periodo di tempo nei villaggi. Esiste la National Innovation Foundation, un osservatorio permanente sul territorio per individuare le invenzioni autoctone più interessanti. Come le pinze per salire sulle palme e raccogliere le noci di cocco. Gli oggetti sono molto eterogenei: a unirli è la relazione tra contemporaneità e tradizioni, che comprende non soltanto l'aspetto artigianale, ma anche quello simbolico. Dal Mahabaratha, stampato (con una certa ironia) sul rotolo di carta igienica Cheerarhan ai personaggi della mitologia indiana riproposti sui giocattoli di carta per bambini Cut.ok.Paste, fino all'immaginario dei film di Bollywood usato da Manish Arora per i suoi abiti.

|

| Bambike - Vijay Sharma |

Per il design indiano potrebbe essere quindi un buono sbocco lavorare sulle piccole economie locali?

Penso di sì. L'India non ha bisogno di passare attraverso il nostro sistema produttivo, perché ovviamente ci si confronta con disponibilità di mano d'opera immense e una grande qualità nella produzione artigianale. Credo che in questa forma organizzativa, fatta di piccole produzioni e di un processo di recupero delle tradizioni artigianali, ci sia la strada giusta per loro. E poi, forse, anche la nostra: l'India non ci offre soltanto la sua visione, ma anche le chiavi per rispondere ai problemi attuali. In questa forte relazione tra tradizioni e innovazione - che è il filo conduttore di tutta la mostra - ci può essere una fonte d'ispirazione anche per noi, ovviamente seguendo modalità diverse.

|

| Cut.ok.Paste - Mira Malhotra |

Il design indiano guarda anche all'Occidente. Come?

Penso che oggi non abbia alcun senso parlare di cultura indiana, occidentale o asiatica: siamo in un momento in cui la cultura è davvero frammentata. È molto difficile trovare identità e compattezze nei tanti flussi globali. La cultura si rinnova e modifica continuamente, quello che invece può servire al designer come strumento di lavoro sono le tradizioni. È sempre più difficile identificarsi con una cultura precisa. Per chi progetta, è un parametro troppo instabile. Però quello che può fare chi progetta è pensare concretamente alle tradizioni, fare emergere elementi dal passato, attualizzarli e riproporli nella contemporaneità. Tanto è vero che gli oggetti che hanno forti relazioni con la tradizione sono anche un po' oggetti transazionali, sono una medicina, un buon accompagnamento, per via dell'uso di tecniche tradizionali o perché contengono dei messaggi simbolici. Ci sono influenze occidentali, ma come parte di un processo biunivoco. Lo stesso Movimento Moderno è nato su ispirazione del Giappone. Non si riesce davvero a dire di "chi è cosa", ma di certo non si tratta di oggetti apolidi, proprio per via di questa riesumazione di diverse tradizioni e della valorizzazione delle culture locali.

L'apporto tecnologico è un aspetto che non avete considerato. Perché?

Quello tecnologico è un capitolo a sé. È un aspetto che viaggia in parallelo al progetto di design. L'India fornisce servizi come call center, semi-lavorati e software, e primeggia nella tecnologia "soft". Molto interessanti sono le due sculture di Ranjit Makkuni, un designer che ha lavorato per quasi vent'anni allo Xerox PARC creando interfacce multimediali e sistemi per l'apprendimento. Nel suo laboratorio, in India, mescola tradizioni e tecnologia. La scultura in legno Re-visualizing a green self, per esempio, racchiude al suo interno sofisticati dispositivi tattili e sonori. Nelle sue mostre, Makkuni ripropone riti e miti attraverso installazioni interattive per fare avvicinare la gente alla tecnologia in modo friendly. In India, c'è una fortissima modernità che s'incastra e mescola con qualcosa di atavico, a creare un incredibile melting pot. Chi è indiano, probabilmente, se ne accorge meno.

Anche l'allestimento è un vero progetto nel progetto.

Kavita Singh Kale si è ispirata alla sua scultura Fragile e al concetto di città in movimento. I fili servono a dare un'idea di equilibrio instabile. È un progetto di grande raffinatezza. Come spiega Avnish: "Molte volte, l'idea di fragilità è collegata a quella di sostenibilità, non bisognerebbe creare qualcosa che è difficile da distruggere. Se gli oggetti sono semplici, vengono consumati e distrutti automaticamente. Questo, secondo me, è uno dei campi che i designer dovrebbero esplorare: materiali sostenibili che, nell'arco di dieci anni, si consumano e si distruggono".'

|

| Elephant, 2010 - Sangaru Sandeep |