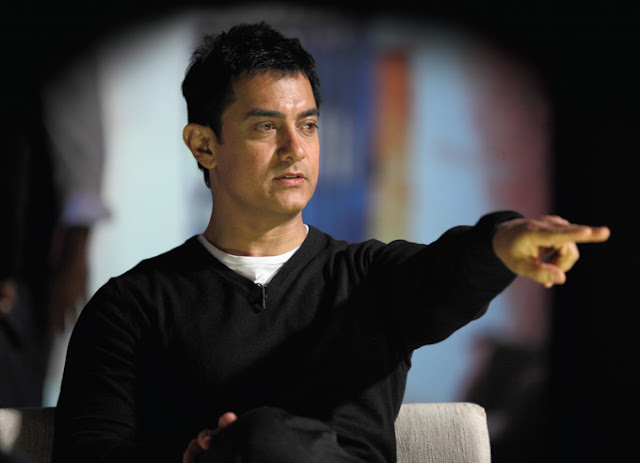

Il 15 agosto 2012, in occasione delle celebrazioni del 65esimo anniversario dell'indipendenza indiana dal dominio britannico, è andata in onda una puntata speciale di Satyamev Jayate, il talk show televisivo più citato e lodato dell'anno. Nel solito duello di cifre, risulta difficile decretare se il programma abbia davvero superato, in termini di ascolti, il successo del leggendario Kaun Banega Crorepati? condotto da Amitabh Bachchan - sembrerebbe di no -, ma di certo l'impatto di SJ è stato potente, principalmente a causa di due fattori: il debutto sul piccolo schermo della superstar Aamir Khan, e lo schema dello show, non originale ma realizzato con grande accuratezza.

Le tredici puntate della prima stagione di SJ sono state trasmesse ogni domenica mattina - orario insolito per un programma condotto da un divo bollywoodiano, ma tradizionale, nella storia della televisione indiana, per una visione familiare - dal 6 maggio al 29 luglio 2012. Gli argomenti trattati non costituiscono una novità, anche se la loro risonanza è stata notevolmente amplificata grazie alla presenza di Aamir Khan, attore popolarissimo e giudicato dai più una figura anomala nel panorama della cinematografia hindi. Si è partiti col feticidio femminile, per poi toccare i temi dell'abuso sessuale su minori, della dote matrimoniale, della corruttibilità della classe medica (scatenando un vespaio corporativo), dei matrimoni intercastali e del delitto d'onore, della disabilità, della violenza domestica, dell'uso dei pesticidi, dell'alcolismo, della divisione castale e dell'intoccabilità, degli anziani, e della carenza di risorse idriche. Ogni puntata è stata commentata da un brano musicale diverso (oltre al tema ufficiale: in tutto 14 canzoni che comporranno un album). Il titolo dello show prende spunto dal motto nazionale indiano, e significa truth alone prevails.

Prodotto da Aamir Khan Productions, SJ è stato trasmesso in simultanea da otto canali privati del circuito Star India e dal canale pubblico Doordarshan. Inoltre il programma, originariamente in lingua hindi, è stato doppiato in tamil, telugu, kannada e malayalam, per abbracciare il bacino di utenza più ampio possibile. Nel canale ufficiale YouTube di SJ sono state caricate le puntate con sottotitoli in inglese. SJ è stato diffuso in un centinaio di Paesi, e persino proiettato, a cura di Star India, in alcune località dell'entroterra del subcontinente non raggiunte dal segnale televisivo. La scelta di realizzare lo show non in inglese ha rivelato l'intenzione di raggiungere il vastissimo pubblico indiano non necessariamente urbano e di ceto elevato.

Nel corso della trasmissione della prima puntata, e per tutta la giornata, Twitter è stato inondato da commenti relativi al programma, sembra con una portata superiore a qualunque altro argomento di origine indiana nella storia del social network. Otto dei primi dieci trending topic in India erano correlati a SJ, fra cui persino #Doordarshan (probabilmente per la prima volta). Il sito ufficiale di SJ è collassato a causa dell'enorme numero di visite.

SJ ha rappresentato uno sforzo notevole sia da parte di Star India - in termini di marketing e di investimenti -, sia da parte del conduttore. Sembra che la campagna promozionale a sostegno dello show sia stata la più costosa mai intrapresa per un programma televisivo, e per la prima volta un programma televisivo è stato pubblicizzato anche al cinema. Aamir Khan, per quasi due anni, ha rifiutato di partecipare ad altri progetti, concentrandosi sulla realizzazione di SJ. La star ha viaggiato per tutto il Paese col suo staff, alla ricerca di storie da raccontare, e ha personalmente incontrato le persone coinvolte. Non solo: Aamir ha chiesto alle aziende per le quali è testimonial pubblicitario, di interrompere la diffusione di spot per evitare una sovraesposizione e soprattutto una commercializzazione a suo beneficio dello show.

Naturalmente non sono mancate le critiche. Alcuni opinionisti hanno ritenuto che la partecipazione emotiva di Aamir Khan fosse studiata e artefatta. Altri hanno rimarcato il fatto che la produzione abbia utilizzato in larga misura espedienti atti a sottolineare la drammatizzazione (colonna sonora idonea, primi piani su spettatori visibilmente turbati, eccetera). Di certo SJ è un programma di stampo populista con dosi di pathos e melodramma. Altrettanto certo è che Aamir sia un consumato attore oltre che un ottimo amministratore di se stesso. Ma in ultima analisi, è positivo che in uno show di così ampia visibilità siano stati discussi problemi scottanti e reali. La spettacolarizzazione può essere perdonabile se piegata a scopi di maggiore diffusione del dibattito che veicola.

Una curiosità: la storia personale di abuso sessuale narrata nel corso della seconda puntata da Harish Iyer aveva in precedenza ispirato il regista Onir per il suo I am. Sempre nello stesso episodio, la star Sridevi ha partecipato al programma.

Si vocifera circa una seconda stagione, e lo stesso Aamir non ha negato la possibilità, anche se per ora l'attore deve affrontare una lunga serie di impegni cinematografici: attualmente è a Chicago per le riprese di Dhoom:3, a seguire lo attendono la promozione e distribuzione di Talaash, quindi un nuovo film diretto da Rajkumar Hirani (PK).

Video della sigla

O Ri Chiraiya: brano musicale che identifica la prima puntata

It's really your life, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 20 maggio 2012

A worthy dream, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 27 maggio 2012

One simple step to increase our GDP, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 10 giugno 2012

There seems to be a civil war out there, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 17 giugno 2012

We are what we eat, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 24 giugno 2012

Thirst in the land of malhaar, Aamir Khan, Hindustan Times, 22 luglio 2012

Aggiornamento del 9 gennaio 2022: sono state realizzate altre due stagioni del programma, trasmesse rispettivamente dal 2 al 30 marzo 2014 (cinque puntate) e dal 5 ottobre al 9 novembre 2014 (sei puntate).

RASSEGNA STAMPA (aggiornata al 10 settembre 2012)

Bravo, Aamir!, Swati Sucharita, The Times of India, 6 maggio 2012: 'The debut episode of SJ depicted not just the stark reality of female infanticide in a hard-hitting, yet, without hitting too hard, non-preachy way, but also showed up Aamir in a new role, that of a competent anchor, which he played to perfection'.

Don't be cynical about 'Satyamev Jayate', watch it!, Sukanya Verma, Rediff, 6 maggio 2012: 'I wasn't too pleased with the aggressive promotional campaign of Aamir Khan's debut on small screen. He is one of the few Hindi film actors with a distinct growth graph from confection to consistent and a rare achievement of pursuing success on his own terms and strategy. Except that the righteous and preachy vibe he gives out in the publicity spots, billboards and soap opera appearances (...) of Satyamev Jayate (...) left me grimacing big time. Marketing and meaningful almost never cross paths, you see. I felt as though my suspicions were confirmed at the start of the programme with a visual of Aamir Khan and his lump-in-the-throat voiceover reflecting the sorry state of our nation and its diverse issues in a lengthy but articulate monologue against the sunset on a vacant beach. It's a familiar tone. (...) Let's be honest, we are comfortably apathetic to wake up at 11am and watch a chat show on India's never-ending troubles - social or economical. But it hits you that the idea is to wake up and smell the shit so that someday, Sunday marks a bright morning for one and all. This is a grand initiative and a sound format into which a lot has been invested - monetarily as well as in terms of research. Will it bring about a change? I don't know. But, at least, it will bring a larger scale of shame to its offenders. To that man who bit his wife's face leaving her deformed for life. To that urban, educated family who didn't want anything to do with the [female] twins. Deriding this show simply because it is hosted by a Bollywood actor who is also a marketing whiz, questions our credibility, not his'.

SJ: more power to you, Aamir, Rajesh Kalra, The Times of India, 7 maggio 2012: 'Aamir has stolen a march, not only over all other actors who have done senseless TV shows in order to reach out to the considerable, and growing, TV audience, but perhaps even the tribe called journalists. It was reality TV of a different kind. There was emotion, there was drama like all other shows. (...) This apart, Aamir’s own consummate acting skills too were in full display. But most importantly, from what one saw, one couldn’t but admire the sort of research that had gone into the subject and effort that had gone into picking the cases. It is something that journalists should normally do. Moreover, his line of questioning and eliciting responses showed the sensitivity that is completely missing when our star journos conduct such shows on TV channels. And the call to action also showed that the program wants to see results, not just create awareness'.

Aamir Khan's concern should be ours too, Saisuresh Sivaswamy, Rediff, 7 maggio 2012: 'It needed someone with a different thinking to make India sit up and think about itself. Given his oeuvre, given his sensitivities, it had to be Aamir Khan who could set television programming right, but it didn't have to necessarily be him. It could have been any of the Khans - all as intelligent as this one, if not more; all as concerned about India as this Khan is, no doubt - or any of the big stars we all love, but the truth is, no one had the cojones (pardon my Spanish) to do it'.

Aamir Khan strikes the right chord with Satyamev Jayate, Parmita Uniyal, Hindustan Times, 7 maggio 2012: 'We knew that Aamir Khan’s ambitious TV project is a reality show about the common man and their problems, what we probably didn’t know was that it attempts to solving these problems by not only providing solutions but starting a campaign of sorts. (...) It’s not that we haven’t read about such incidents before in newspapers and television. We have, but what’s different is that the show succeeds in convincing people of the outcomes of such practices better than a government campaign on female infanticide. (...) The format is quite crisp. Talking about the emotional connect, there are moments when your eyes well up with tears, but the various segments ensure there’s more content than emotional drama. (...) It is rather interesting to note that when journalists turn entertainers by doing mindless stories on superstitions, entertainers like Aamir Khan have to step in to do what journalists are supposed to do - make a difference. The show is a classic example of that'.

Aamir Khan's SJ played it safe, Sheela Bhatt, Rediff, 8 maggio 2012: 'It is very interesting to see that in a country where the mainstream media is limiting itself more and more in making the choice of subjects and is drifting away from national priorities, Aamir Khan is arriving with a mega show to occupy this vacuum. Aamir has to be applauded for picking a serious issue that has afflicted and shamed India. One is not trying to denounce him or his efforts. But, at the same time, his programme's format is too predictable and flat. It hardly carried any nuances of the complex subject. (...) The issue of gender bias has a historic context and it shows the ugly side of the human psyche and Indian family traditions. SJ was neither hard-hitting enough nor did it show any new facets of the issue to usher in change, leave alone revolution. It played safe by making us cry. Only cry. Sure, Aamir denounced forcefully the monstrous idea of killing the girl foetus but, in some moments, in some frames, he was making an attempt to appear engaged which did not look natural. (...) The format of SJ has to be more profound. The present format looks like an assembly-line production. Many such programmes have come and gone. One does not need the great actor Aamir Khan to make people cry. (...) Aamir should not touch the emotional nerve of his fans too soon and too frequently. 'Drama' or 'melodrama' defuses the focus on stark reality. Tears are an obstacle to touch the core of the issue. To make an impact Aamir should not make us cry, he should make us angry, outraged'.

Aamir couldn't show genuine feeling!, Subhash K. Jha, The Times of India, 11 maggio 2012: 'Playing the role of reformer is not easy. Aamir has mastered the art. Sadly the mastery showed up on camera on that historical Sunday morning. His influence in the field of cinema is undoubtedly exemplary. And honestly, if I had to choose one entertainer to take us through the horrors that pervade lives in non-urban cultures I'd choose Aamir. He has the clout. And the gravitas. Lamentably he just couldn't bring enough genuine feeling to the table when he spoke to the victims of female foeticide in the first episode of his long awaited serial SJ. And it's not entirely his fault. The role of the crusader seemed to have been embossed on his sleeve rather than his soul. The lines were rehearsed, as they had to be. You can't film misery without pre-written lines. And that's where the difference of perception crept in. The women who had suffered hadn't rehearsed their lines. Their appalling experiences seeped out of their lacerated souls. The tears had dried up. Unfortunately the camera doesn't respect invisible tears. Our host had to keep that in mind. TRPs are important too, you know. (...) Aamir doesn't quite fit in. The spirit is willing. But the connectivity is weak'.

Aamir's TV debut gets fewer eyeballs than most celeb shows, Varada Bhat, Rediff, 16 maggio 2012: 'The title sponsorship has been hawked at Rs 16-20 crore, while associate sponsors have paid Rs 6-7 crore. The 10-second advertising spots are sold for around Rs 8-10 lakh, according to media buyers. The show has eight sponsors, with Airtel being its presenting sponsor and AquaGuard the co-sponsor. Coca-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, Skoda Auto, Axis Bank, Berger Paints and Dixcy Scott have been signed up as associate sponsors. The show is touted to be one of the most expensive television productions on any Hindi general entertainment channel, with costs per episode running up to Rs 4 crore. Other celebrity shows cost less than Rs 3 crore per episode'.

Intervista concessa da Aamir Khan a Shoma Chaudhury per Tehelka, 19 maggio 2012:

'What triggered the idea for you?

(...) The idea is to try and bring about an attitudinal change. We often want to point fingers at the government (...) but there are many issues for which we are the solutions. We have to decide whether we want to think a certain way or not. Crimes like these are planned in bedrooms but you can’t have a policeman sitting in every bedroom. So the entire attempt is to talk to every Indian and see whether we understand an issue, and if after understanding the issue fully, we can have a change of heart. Through these shows, we’ve tried to bring out the personal angle, the sociological angle and, depending on different issues, the economic and, sometimes, the legal angle. Sometimes we have focussed on the way forward because we’ve found somebody has found a solution in different parts of the country. Can we learn from that? This is an effort to take 13 topics, one at a time, and really attempt a 360 degree perspective on it. What I understand from it is what I am presenting. For me, the journey is an internal journey of my change. I believe each one of us has to see if it makes sense to them.

After the idea struck you, did it take a long time for you to cave into it? To decide to risk moving from cinema to TV.

It started with Uday Shankar from the Star Network offering me a game show. But I wasn’t interested so he said, “Okay, think of something you’d like to do.” When I thought about it, I was pretty clear only two things would interest me on TV. Either something which is fiction, which is not suitable for films and needs a longer, episodic telling. Or a show which has the potential to bring about dynamic social change. He said, “Okay, tell me when you are ready.” For the first four to six months, I thought about it alone. (...) Once the thought became slightly more concrete, I called Satya (Satyajit Bhatkal), who is a friend of mine and asked him, is this idea making sense to you? I needed someone I could trust completely. Being a celebrity it becomes difficult for me to go to the grassroots and have people talk to me in an unbiased manner. So I needed people who are unknown, who can go out there, but whose ears I trust, whose eyes I trust, whose sensibility I trust, whose sense of judgement I trust, whose value systems I trust. And that is Satya, whom I have known for 30 years now. I told him, he got excited, so we put together a team of four. (...) Initially I said, let’s work for six months, start our research, then we’ll take a call. I said, “I want you all to know this is still just a process. It may or may not land us a TV show. But at the very least, we’ll all learn something.” After six or eight months, all of us felt it was working. So a good two years after Uday had first come to me, I called him back and said, “I’m ready.” Did I feel nervous about it? I always feel nervous about everything I do. So that’s nothing new. Obviously, we worked with a lot of passion and love, so we want the show to connect with people. And that concern is always there whether it will connect or not. But the reaction to the first episode has been so overwhelming and so heartwarming, it really brought tears to all our eyes. We are thrilled.

What was the toughest part to crack about the show?

See, all these issues are actually already covered by print or television media. What I felt is if we cover them in a very knowledge-based way, or in current news style, the stories have no emotional impact. My purpose is to actually touch people’s hearts. That is the thing that we spent a lot of time figuring out. What I find when I research a topic is the same, but if I present it to you in an interesting and emotional way, it can change you, and change the way you look at or think about something.

Television viewers are famously fickle. Was there any resistance from the channels to your desire to make the show one-and-a-half hours?

I have never done TV in my life, so it’s not a medium I know much about. So yes, the length was always an issue. I wanted it to be an hour but I found I couldn’t fit in all the aspects of the research because in one hour, remember, there are ads also. Right now, I am getting 66 minutes of content in a 90 minute slot. These are huge topics. It’s very difficult to tell you all about it in one-and-half hours. But we are trying to. You are right, TV-viewing habits are fickle. People tend to switch channels. The reason I chose the Sunday morning slot was because it’s considered graveyard time. But that’s the time I wanted, when nobody is watching anything else. I did not want people to have anything competitive to switch to. I wanted people to switch their TVs on for my show at 11 am and if they didn’t like it, they could switch their sets off. That’s an option you always have. But I wanted your commitment. I wanted appointment viewing. As an audience, I wanted you to take that step towards me. (...) I was requesting you to come.

Personally, what was the biggest shock or learning for you from the foeticide story?

We often think people who are poor don’t want a girl child because of dowry and stuff. These are the preconceived notions. It was a shock for me to realise that people who are urban, well off, and highly educated are more likely to indulge in female foeticide. One of the things we always feel is, why is our country so backward? We feel poverty and lack of education really pulls us back. Correct? This is our thought. But here with female foeticide, I realised it’s got nothing to do poverty, in fact the rich indulge in it more. It’s got nothing to do with education, in fact, educated people do it more. If, intellectually, we are not rich, if our thoughts are not rich, how does it matter how much money is in our pockets? If I am not a sensible or sensitive person, then how does it matter if I know the answer to difficult physics or economics questions. That was the big learning for me in this episode. And, of course, the fact that most men don’t know what a woman goes through. Men just don’t understand. (...) There was also this realisation that there are some crimes we don’t do alone. Who (...) is your partner in crime? A doctor! Isn’t it amazing? A doctor is someone who is supposed to save lives. But it’s a doctor who is telling you the sex of your child. Just because they wear white coats and are in a hospital room you don’t recognise it to be a crime. But it is illegal to find out the sex of a child.

In terms of the breadth of research that the team did, how many personal stories did you actually get? Were there any that particularly touched you?

We got many stories, much more than we could put in. The three stories that are in the episode really touched me, and I found it very difficult to continue with my conversations. What you do not see on TV is the part where I break down. We had to edit that out from the telecast because obviously you can’t have me crying for 10 minutes on screen. But there was a fourth story that did not make it to the final cut, and that is the one which really made me cry. It was a girl who didn’t want to come on camera. We had shot with her and blurred her face. And she explained what she went through in a very, very raw and emotive way, as opposed to a more cohesive narrative. What she said is, when her child was aborted, the child was five to six months old. So she had to give birth to it, she had to deliver it after it had been killed. She explained that they put a tashla, like a metal bowl, in which the baby, the foetus, came and fell in. And she said that the sound of my baby falling in, that is something that I just cannot get out of my system. Even now, when I’m in the kitchen, and some pyaaz falls into the pateela which we cook in, I remember that sound and I just break down.

You couldn’t go with it?

We were at 66 minutes already and we couldn’t change that. We had to choose what to drop. In this case, the girl is unnamed. Even in the show we call her Anamika because she wants to keep her identity unrevealed and we respect that. The face was made fuzzy. A lot of people said the connect will be less because we can’t see the person. I didn’t agree with that. She speaks so desolately it’s difficult to get her out of one’s head. Also, the other three women are no longer with their husbands but this woman still is. When she gave the interview, she actually didn’t tell her husband. She was just very disturbed by the incident and wanted to talk about it. So she called (...) when her husband was not around. That’s how important it was for her to speak about it. Then a couple of months later, she told her husband about the interview. At first, he was upset but then they spoke about it. For the first time, he realised what she’d been through and apologised to her. Till then, it was an unspoken thing between them. So all that came pouring out. Then I spoke to the guy and he came and met me. He said, “Now I realise what happened, what my wife went through. I shouldn’t have done that.” It was all very cathartic and moving but would have taken even more time to present.

What made you stop all your advertising contracts for this year?

There’s no logic in that. There’s nothing wrong in doing an ad for a product you would like to endorse, and if there’s something wrong, you shouldn’t do it in the first place. It’s not as if I’m endorsing cigarettes or alcohol (...) or something. Two of my endorsements were getting over before this show came on. The other three, the contract was going beyond the date, but I requested the client to relieve me while the show is on. It’s very important for me that I don’t do ads. And I’m happy to say they respected my emotions. Then there were two three other people who wanted me to sign on and I said, “No, no, I’ve stopped doing ads.” I just felt that while I’m doing this show I didn’t want to be selling something. I don’t know how to say it. It didn’t feel right to me.

How much personal time have you dedicated to this?

(laughs) All of it. Professionally, in the past two years I’ve shot for a film for about four months, Talaash. Apart from that, all my time has gone here.

You bring a sort of purity of intent to your creative commitments. Then once it’s ready, you mount super canny marketing strategies on them. How did you work the marketing strategy for this?

I’m thrilled with Star, I have to say. In the first meeting, when I told them I had the concept ready, it didn’t take two minutes for Uday to say, “I’m on.” I told him I want multiple languages, I want Doordarshan, and these are all difficult things I’m asking for. He was bang, Doordarshan, yes, multiple languages, yes. Sunday 11 am - are you sure, because nobody watches TV at that time. I said, “I’m very sure.” So he said yes. This was their attitude. Very dynamic, very supportive. The creative team (...) were fantastic to work with. I’d feared that when I enter TV, they may want me to compromise on my, as you say, purity of intent, but they were as pure about it as I was. (...) Everyone down to the digital team. The agency they hired was O&M, and they asked me what is it you’re doing. I gave them the whole explanation, then said all our sessions are recorded, either on a dictaphone or a camera lying around, like making notes. Why don’t you have a look, it’ll give you an idea. They spent the week looking at the stuff, then came back and said our campaign is ready. They said these conversations you’ve had about shaping and conceiving the show are so interesting, that should be the campaign. It will be true to the nature of the show. So that’s how the idea came about. Of course, Star has put its full marketing might behind it, plus we had Doordarshan’s marketing. It’s never happened before. A show on a major general entertainment channel, plus on 8 of their other channels, whether it’s Star Prabha, which is Marathi, Asianet the number one Malayalam channel, Vijay in Tamil Nadu, and in Andhra, they’ve taken another channel which is not their own. This kind of platform even cricket doesn’t get; it comes on like one channel and one Doordarshan. But I was really clear I wanted it this way. If you really want to bring about strong dynamic, attitudinal change, then you have to reach people in their own language. These problems are common to everyone. (...) This was thought out in a very deep way. I was planning for a very long time that I want it to reach everyone, so it doesn’t end here. Through the week, I’m on Radio Mirchi, All India Radio, Big FM, Vividh Bharti, my articles come in a newspaper of every language. We have a very strong Internet site. It’s a full blitzkrieg.

Has doing these 13 stories changed you?

Yes. It has. I’ll talk more freely when all 13 are over. But let me just say that I and the entire creative team, all of us are going to go for professional therapy. We’ve been through so much raw emotion, I’ve become very brittle. I’m not kidding, we’re all going to go for group counselling. We talked about it and we really need to do it. That’s the kind of impact it has had on us'.

A seguire, nella stessa videata, The power of one di Sunaina Kumar: 'On Twitter, the show generated the single largest reach for any Indian content so far. (...) On Sunday the website for the show crashed twice, it became the top search in India on Google Trends, and in a span of a day as social scientist Shiv Visvanathan said, “Aamir became the most well-known sociologist in the country.” He ties it to Aamir’s earlier experiments with national and social issues, as brand ambassador for Incredible India’s (...) campaign, his clarion call to apathetic youth with Rang De Basanti, raising sensitivity to disability through Taare Zameen Par, critiquing our education system in 3 Idiots, and involving himself with polarising projects. (...) In SJ, we see him as someone who has acquired supreme confidence about his point of view and his ability to convince others of it, occasionally pedantic, mostly restrained. Social commentator Santosh Desai says it is the “consummate marketer” in him. (...) Benjamin Zachariah, a historian at University of Sheffield, says, “He knows that the best way to enable his critique of national life is by emphasising his nationalism. It creates the legitimacy he needs to raise difficult issues.” (...) Media personality Pritish Nandy says, “SJ falls in the crack between news and entertainment. What it needs now is more journalistic muscle, cutting edge, less tears and more dispassionate reporting. If Aamir wants SJ to be taken seriously, he must behave on screen like a real journalist, not someone trying to manipulate the audience’s emotions. That is the actor’s job.” SJ is one of the most lavishly produced shows on Indian television, a show that uniquely marries social and commercial considerations. Much has been made about the cost of production of the show, the marketing juggernaut, the advertising rates and the fee Aamir is charging, even though he has annulled all his advertising contracts for the year on ethical grounds'.

Why does Aamir cry every Sunday?, Anuradha Varma, The Times of India, 27 maggio 2012: 'Newscasters are calling Khan a journalist, and perhaps, for the first time, a case can be made for a talk show that has become more popular than its celebrity host - a recent exercise in trend spotting by Google Insights for search, a data comparison tool, revealed that by the second week, netizens were searching more for the show than for Aamir Khan. To put that into perspective, consider this: 12 years after Kaun Banega Crorepati first aired, Amitabh Bachchan still remains more searched for than his show, online. Will social talk shows replace reality TV as the new form of entertainment? (...) Let's put our mind to what's making it so popular.

- Judicious use of tears. While experts and viewers agree on the good intentions behind Khan's television debut, it is interesting to note the pitch-perfect reactions of the studio audience and the host during the show. Depending on what is said, the audience looks teary-eyed, shocked, angered and sometimes, just plain disgusted. (...)

- Game changer for real? (...)

- The celeb factor. Aamir Khan's impact is clear. While he charges an estimated 4 crore per episode, he also reportedly asked a watch and electronics brand he endorses, to refrain from advertising on SJ - a move that would only enhance his credibility and trustworthiness. (...)

- The host's involvement is central'.

The holiness of the heart's affections, Aveek Sen, The Telegraph, 19 giugno 2012: 'In all the publicity stills, Khan’s face has that solidly focused, almost driven, look - alert, outraged, but holding the emotions back because his sense of urgency tells him there’s no time to waste. His eyes look out towards some distant horizon (election candidates often have that visionary look in their posters). Or else, he is intently listening to a victim’s testimony, fighting back the tears that well up in instant empathy. His empathy is instant and humility endless - and both instantly, endlessly enacted. (...) It is good market strategy for cuteness to age into conscience, if it doesn’t want to lose its monopoly over hearts. Empathy and afflatus have a readymade language - in popular cinema and on the internet. This language puts no strain at all on either thought or action, and that is the mindset and skill-set on which the success of a series like SJ depends'.

Does SJ work?, Pritish Nandy, The Times of India, 8 luglio 2012:

'For the past few weeks I have watched Aamir Khan on TV raising crucial social issues on his show. I like the way he does it though I know many who don’t. I know why they don’t. The flaws are obvious.

To begin with, the show gives us the distinct (if somewhat false) impression that it intends to repair social ills. But as you keep watching it, you realise Aamir is a voyeur, not a reformist. He is not a voyeur like we journalists are. Journalists don’t just point out social ills. They campaign against them. They stick their neck out for what they believe in. Aamir does neither though he adopts the tone and demeanour of a journalist. He presents the problem and then steps back, expecting the political system to repair it. And that, as we all know, never happens. So the show is an escapist tear-jerker. It will not change the world around you. It does not even intend to.

That makes it doubly frustrating. When someone points out what is wrong, you expect the person to set it right (which a leader can do, if he really wants to) or put so much pressure on the political system that it is forced to act (as a journalist tries to do, not always with much success). Satyamev Jayate attempts neither. Aamir sheds a few tears. So do we and then, next week, we move on to another problem, another tear jerking show, another catharsis. No one knows what to do with all these sad stories. If they had appeared in newspapers, people would have filed PILs or RTI queries to see how they could push the issue to a point where the Government is forced to act. For, as we all know, no Government works on its volition. Since Aamir is the interlocutor here, they expect him to do that.

Movie stars may be larger than life on screen. But when it comes to taking on the political system, they have no clue how to do it. In fact, I doubt if they want to. In real life, unlike their imagined screen roles, they do not see politicians as enemies. They see them as peer group: People with power and money. Journalists, on the other hand, often put their life on the line chasing stories. I know because like many others I have faced countless court cases, harassment, intimidation, death threats. But we take it in our stride because we see it as our job. A movie star does not see exposing the truth as his job. His job is creating illusions. So while he may occasionally endorse a cause, he will be the first to step aside when things get rough. I don’t blame them. It’s not what they set out to do.

That’s the fatal flaw of the show. Aamir does his best to beat it but it is not in his hands to do so. He has to go back to making movies and this, after all, for him is just another TV show. It is not his life. Yet by adopting the tone of a journalist, he makes it appear as if he is truly and deeply concerned with the issues he has raised. That is where the contradiction lies. And that is where Satyamev Jayate fails. It fails because Aamir cannot and will not see the issues through to a solution. He is a great guy but not a change agent. He is an actor, a role model, a charming claimant to the role of a journalist. But he neither has the will nor the persistence to bring about change. Nor does he have the time. This is, for him, a TV show. Not his life, nor the purpose of his existence.

But yes, Satyamev Jayate will eventually bring about change simply because it happened. Everything we do leaves its impact, if not right then and there, at some later stage. That is why it’s important the show happened. It’s important Aamir saw it as a purpose albeit for a 13 week period. Now life has to pick it up. History has to assimilate it. You and I have to take it ahead. Aamir’s job will be over after the 13th week'.

Intervista concessa da Aamir Khan a Faridoon Shahryar per Bollywood Hungama, 18 agosto 2012: prima, seconda e terza parte

I've grown as a human being, Shoma Chaudhury, Tehelka, 18 agosto 2012:

'Aamir Khan could have done nothing. Privilege is a blessing very few entitled Indians use for anything more than lining the already silver clouds they inhabit. But Aamir stepped up and created Satyamev Jayate (SJ), a show unprecedented on Indian television. It wasn’t a risky thing to do in the classic sense: there were no struggles for money; no threat to life; no power structures breasted. But there were the possibilities of failure, rejection, loss of popularity - the breath cinema stars live on. Aamir didn’t linger to calculate those ephemerals. Having decided to do the show, he mounted a massive and staggeringly meticulous operation to get it right. With his core team of three, Satyajit and Svati Chakravarty Bhatkal and Lancelot Fernandes - co-travellers, he says, he’d have been crippled without - Aamir went about acquiring 1,600 hours of background footage, capturing personal testimonies from across the country, ferreting out experts, statistics, legal positions and solutions. On the sets, he had 10 hidden cameras so guests wouldn’t feel their intrusive eye, and generated more footage per episode than entire seasons of other shows on Star TV Network.

There are many other impressive statistics. Over a billion mentions of SJ on the Internet; between Rs 27 lakh and Rs 2 crore raised for each of the organisations mentioned in the 13 episodes, and many real-time administrative and political impacts. But Aamir’s real achievement is to have leveraged his stardom to reposition the moral spotlight on public discourse, and bring scale, sensitivity, nuance and a civilising intelligence to issues of burning importance, neglected too long by the media. The intangible ripple effect of this will always remain unmeasured: thought seeds sown in unknown hearts; ginger windows opened in anonymous minds. Emotional transformations unrecorded.

There have been carpers who have slung specious shots at Aamir even for this. Journalists who’ve sneered that SJ is a personal brand-building exercise. Tweeters like Taslima Nasreen who’ve wondered why SJ should get so much attention when there have been civil rights groups fighting in the trenches for so long. And other sundry critics who’ve claimed SJ is the noble equivalent of Star’s saas-bahu [suocera-nuora] serials.

These seem nothing but the pincer moves of the habitually negative. Anyone who sees the show would know that SJ does not set itself up as competition to civil rights groups: it sees itself as their amplifier. Within the confines of a television show, SJ has done everything it possibly could: it has made difficult issues like female foeticide, alcohol abuse and water crisis seem the most engrossing of stories with a rare dignity and devotion to complexity. In a country parched for serious engagement, this is welcome rain. (...)

Coming from a world of entertainment, do you feel your intense immersion in issues through SJ has changed you? Looking back, do you feel you were in a cocoon before?

That is certainly true. It’s been a huge learning. At an emotional level, the journey of these two years - and the background research and testimonies is much vaster than what you see on the show - has been very shocking and heartbreaking and difficult to deal with it at times. But it’s also been extremely inspiring. You marvel at the human spirit, at ordinary people who have no obvious signs of power like money or position but show such courage. But the biggest change is at the level of information, my knowledge of what is happening around me. Take a simple thing like I didn’t know where the water in my house came from. I had no idea till we began our research. Now I know it comes from a place a 100 kilometres away and that people living there do not have water because of me. Or take the issue of untouchability. Given my upbringing, it was difficult for me to believe it’s so rampant even in a city like Mumbai. So much has come to light for me. I feel I’ve come to understand - actually understand is the wrong word because I’m still grappling to try and understand it, but I have come to know so much more. At least in terms of observing what is happening around me, I have improved. I feel I’ve grown up as a human being. The other change is, at the level of human interaction. I’ve lived a very sheltered life. Until we did this show, I’d probably never have had the opportunity of meeting people from so many different regions, languages, backgrounds and social strata. That has been extremely enriching.

Are you finding it difficult to fit back into your own circle? Do you feel an information divide separates you from their concerns now?

Well, not yet, because right now my circle is still limited to the SJ team. But I have to say this. I recently started shooting for Dhoom:3 and I found the team on set - technicians, spot-boys, assistant directors - everyone had been watching the show and they wanted to discuss the people or issues on the show or tell me their own stories. I think a lot of people around me, who otherwise would not have been aware, have connected with the show, so I don’t find them that out in the cold. There’s also something interesting I want to share with you. We’ve hired a company called Persistent to do the analytics on the show’s impact. They have a team of 500 people whose brief has been to capture all the discussions, messages or anything said about SJ in the last few months in the digital domain. They have collected more than a billion traces, which makes SJ the most talked about show on earth. I asked this team one question: can you tell me in one sentence, what is the one thought that emerges for you from the millions of messages that have been flying around on the show? They thought about it and the one line thought the team has come back with is: “I am not alone.” That’s a very big thought and also a very personal thought. Because people shared such intense personal stories on the show, the response has also been very personal. After the show on untouchability, for instance, we got many messages from young people saying from here on, at least in my environment, I am never going to discriminate. That’s a very big statement. In other ways, for instance, people who’ve suffered from child sexual abuse have realized that almost one out of every two people has suffered something similar so they feel less isolated. So to return to your question, am I able to connect to people around me after SJ, the answer is yes. Because they have all been part of this journey, I feel I’m able to connect even better. (...)

There has been some criticism of the show from some quarters. That at times it reinforced stereotypes, for instance, of women as appendages of men. That the show dumbed down some of its messaging, or was not radical enough or skirted some uncomfortable issues. How would you respond to this? While constructing the show did you hold back at any time so you could connect with masses on what is essentially a general entertainment channel?

No, not at all. At no point did we do that. Every one of us in the team - and specially Satya Bhatkal, Svati Chakravarty and Lancy without whom this show would just not have been possible - have approached this with a great degree of integrity. We have not compromised on anything. What you see in the show is what we have felt. Never once have we felt, lets not say this because it’s not a popular thought. Why would we pick up issues of untouchability or dowry if we wanted to avoid disturbing topics that would alienate my audience base? As far as gender equality goes, there is no doubt in my mind that we are strongly recommending it in everything we have said. (...) If some people didn’t get that, I guess that’s there problem. Quite honestly, I don’t feel the need to spend my time responding to this criticism because there are some people who are very cynical and have a negative approach no matter what you do. Thankfully there are just a handful of them. So, to those who say I played safe or did this to earn money or build my image, my simple response is they should certainly convey what they want to in a programme when they make it. They are free to do that. As far as I am concerned, we left absolutely no stone unturned in following what we believe in. Also, you know Shoma, we had almost 15 guests on each show. If even one of them had felt that we did not accord them enough dignity or felt disappointed or regretted coming on the show because they did not like the way we portrayed their issue, I would have felt we had failed. That is a criticism I would really have taken to heart.

Did you have to struggle with your stardom and how not to make the show end up being about you? Is that generally a riddle for you? That, on the one hand, you’re able to do certain things only because you’re a star with a certain brand value yet you don’t want to be the focus.

No, that was not a struggle for me at all. I’m really grateful that the entire Star Network just allowed me to do what I wanted and was extremely supportive. Initially I was a little worried that, being a general entertainment channel, their creative people might try to skew the show in a particular way. (...) We were very clear from the start that here is an issue and we ourselves want to understand it in all its complexity and convey that to our audiences. I’m merely the via media, asking questions, listening, the medium through which the strength and expertise of survivors and experts or whoever is in front of me is reaching people. I couldn’t have known this but Satya told me that just as an exercise, because we spend so much time on the edit table, he had calculated how much time I talk on the show and how much others and it turns out I talked for less than 25 percent of the time. So no, that was not the struggle. The struggle for me was, will I be able to have a meaningful conversation? I’m not a trained journalist; I have no experience in asking questions. For 25 years, I’ve always answered questions. And I’ve noticed that with some journalists I just clamp up, I don’t know why but I don’t feel like talking to them. And there are some journalists with whom I find I’m suddenly unloading and opening up and saying things I would have otherwise not thought of telling anyone. For SJ, I needed to speak to people about very traumatic and personal experiences. I was frightened about this all the time. Would I be able to connect in a way that would make each of them feel like sharing their life story with me, would I be able to draw them out? To make sure we broke the ice, I met all my guests for lunch a day before the shoot. Then in the studio, we shot for almost 8 hours for every episode that ultimately would last an hour. With many of the personal testimonies, we let the conversation run for hours because I did not want to hustle them or force their story down any preset agenda. We wanted them to tell it at their own pace. (...) And with each story the challenge I felt was, how can I make sense of this? What sense do you make of it? How can you make things better for the person? How can I ask them questions when all you want to do is just hug them and somehow protect them. Those were my challenges, not how to deal with my stardom.

You have been critical of the media in the past. Do you think SJ stepped into a vacuum left by the media, which should really be focusing on all these issues?

It’s not strictly true that the media doesn’t report these issues. A lot of our research, in fact, is based on media reports from the past. I guess the issue is there is not enough analysis in the media; you get surface facts but not the reasons why things are happening or how they affect people. Two, I think certain sections of the media are really disconnected from ordinary people and what they are concerned about. What do I want to know when I’m reading a newspaper or turning on the TV? Do I only want to know about some political game that is happening? Or who will be the next President? For sure, that is news but I think too much of emphasis is placed on political gossip and fighting which feels very immaterial to people’s lives. (...) People are interested in issues of water and pesticides and medicine and foeticide but the dots have to be joined for them. How does all this impact them? I think we were able to join the dots for our viewers. (...)

One of the things I liked about SJ was that the personal stories were handled with a lot of dignity and delicacy. The show could so easily have turned into a trauma fest, where you just juiced people for their stories. But this did not feel voyeuristic in any way. (...)

SJ could have just focused on personal stories. They were so engrossing each of them could have carried a whole show. But our intention was to take an issue and understand it from a 360 degree view - the personal, political, social and legal aspects. We also wanted to empower our viewers by telling them about their rights, where the law stood, get experts voices working in the field for 30-35 years and also bring you people who have found the way forward. (...) If you are living in a village, this is what you need to do. If you’re living in a city, this is what you need to do. (...) Our basic point was that unless we start thinking of these issues collectively as a society, ultimately, it’s not going to be good for anyone either.

There were some reports that the show did not get the TRP rating Star was expecting. Is that true?

If it were true, why would Star want a second season? But either way, I don’t think that’s important. I don’t give any value to TRP ratings because my common sense tells me that seven thousand boxes across India is not going to tell me what India watches. (...) My assessment of the show comes from other sources. I’ve already told you about our feedback from the internet and, mind you, internet penetration in India is just 15 percent but, given that there have been over a billions mentions of SJ, it feels as if we had almost 100 percent engagement from that segment. Now with the 85 percent of our population who do not use the internet, how will I ever know how many of them watched the show? For that, I did several things. I went on every radio channel. Radio Mirchi, which covers 25 centres, Big FM which covers 45 centres, All India Radio which covers 174 centres, which means it reaches even where there is no TV. The feedback I have got through being on radio is absolutely unbelievable. Towns whose names I had not heard, villages which I didn’t know even existed. All sorts of people have called in and said their entire mohalla watches it. (...) So I have no doubt about the scale at which SJ has connected with people.

Have there been a lot of real life impacts from the show? How has the political class responded?

All of it’s been really dynamic. We’ve had a lot of calls from farmers, for example, asking about organic farming, so my team made an all-India list of every farmer doing organic farming, with a state-wise break up and contact details and I read this out over All India Radio. After I met Rajasthan chief minister Ashok Gehlot, he consulted the Chief Justice and set up a fast track court on female foeticide within 48 hours. Then, already five or six states have announced that they would be providing generic medicines in their states like Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu have. There have been innumerable raids on illegal clinics and many people have lost their licenses. After the healthcare episode, Shanta Kumar, who is the Chairman of the Standing Parliamentary Committee on FDI in pharmaceuticals, asked us to share our findings with him, so we spent three hours with his committee in Parliament. Just a couple of days ago (...) the Maharashtra water minister came to my house at seven in the morning to discuss ways of combating the water crisis in the state. Chief Justice of India, Altamash Kabir told us he was going to take up the issue of the Vrindavan widows and I think the Supreme Court has already taken suo moto notice of it. So a lot has been happening off screen as well'.

Star Power, Bobby Ghosh, Time Asia, 10 settembre 2012:

'The Aamir Khan sitting across from me in the office of his elegant, art-filled apartment in Mumbai's tony Pali Hill is (...) all grown up and very, very serious. His legs are folded in the lotus position on his favorite perch, a faded green armchair. His palms are joined as if in prayer, with both forefingers grazing his lower lip. His back is perfectly straight. It is the ideal posture to meditate on the question he has himself raised: "What is the role of the entertainer?" After waiting just long enough to make me think I'm required to respond, he supplies his own answer: "It's to bring grace to society, to affect the way people think, to make the social fabric stronger."

That would be grandiose coming from almost any movie star, but 47-year-old Khan, one of India's most successful actors, is trying very hard to live up to his ideal. Over the past decade he has acted in, directed and produced a string of movies that artfully straddle the demands of popular cinema and that desire for grace. Now, with his groundbreaking TV show Satyamev Jayate (....), he has dispensed with commercial considerations to indulge his conscience. With it, Khan has taken on the mantle of the country's first superstar-activist.

The show, in equal parts chat and journalism, casts an unblinking spotlight on some of India's ugliest social problems. Khan is its creator, producer and host, and he has invested it with his star power - and his credibility. It's a ballsy move, and potentially jeopardizes his status as the beloved idol of millions. After all, the subjects his show tackles (...) are precisely the sorts of harsh realities from which many of Khan's fans seek escape in his movies. (...)

It might just pay off - for India as much as for Khan. By the time the 13th and final episode of the show's first season aired on July 29, it had notched up an aggregate TV audience in excess of 500 million. (A special 14th episode was broadcast on Aug. 15, the anniversary of India's independence.) Many more millions followed the series on radio, watched episodes online or picked up threads of the discussion in their newspapers. It may be impossible to calculate how much total benefit Khan has brought to Indian society, but there's plenty of anecdotal evidence that the actor long typecast as a singing-and-dancing romantic lead is enabling some real change.

Only days after an episode on the sexual abuse of children, the lower house of India's Parliament passed a long-overdue bill to protect kids from such molestation. Another segment, on the exploitation of "low caste" Indians, led to a meeting and discussion with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. A show about crooked doctors brought an invitation to testify before a parliamentary committee, a first for an actor. It's not only the high and mighty who are reacting to Khan's high-wattage advocacy. After the episode on female feticide, the chief of Budania, a small village in Rajasthan state, vowed to set the police on families that sought gender-determination tests and abortions.

Not all the response has been positive. A doctors' association demanded that Khan apologize for the episode on medical malpractice, saying it unfairly portrays all doctors as greedy and crooked. (Khan denied that all doctors were so portrayed and refused to apologize.) Some commentators have carped that the star's prescriptions for the social ills he identifies are too woolly minded and impractical. (Sounding frequently like a self-help guru, Khan indicates that India's problems could be solved if all Indians resolved to solve them.) Others suggest that the actor fakes the emotions he displays during the show's more dramatic moments. (...)

Nobody questions, however, that Khan has forced his audience to confront unpalatable truths about Indian society. Even journalists with a long track record of covering social problems acknowledge that Khan's star power has helped make people sit up and listen. "We've been covering these issues for years," says Richa Anirudh, the anchor of Zindagi (Life) Live, a Hindi-language news show that tackles themes almost identical to Satyamev Jayate's. "But when [Khan] brings them up, they naturally get more attention."

The Bollywood Identity

Can a movie star affect the mores of a nation of 1.2 billion? It might just be possible in India, where a national obsession with cinema, unparalleled in the world, gives popular actors an influence beyond the imagination of Hollywood scriptwriters. Indians are voracious movie watchers: collectively, they buy over 4 billion cinema tickets every year and watch over 1,200 films in a dozen languages. (In comparison, the average annual output of Hollywood's major studios and subsidiaries in the past decade is barely 180, with Americans buying 1.28 billion tickets a year.) Scores of Indian TV channels deliver an unending supply of reruns, and pirated DVDs of current releases as well as classics sell in the millions.

But you don't have to be in front of a screen, large or small, to come under the thrall of Bollywood. (The term, originally attached to Hindi-language movies made in Bombay, or Mumbai, is often used to describe all of Indian cinema.) Giant billboards advertise the latest releases or feature movie stars endorsing everything from automobiles to mouth fresheners. Every day of the year, readers of major Indian newspapers receive an eight- to 16-page supplement of cinema-heavy celebrity coverage.

All of this adds up to a national culture of fanatical star worship: only Brazil's adoration for its top soccer players comes close. "If you're a movie star in India, you're both a god and a favorite child," says Anil Kapoor, who had enjoyed that status long before international audiences saw him as the swaggering quizmaster in Slumdog Millionaire. "People give you incredible reverence, but when they talk about you, they use your first name, like you're a member of the family."

Yet, for all their outsize influence, Bollywood's biggest stars rarely embrace causes, even uncontroversial ones. (...) "Many [Indian actors] are good-hearted, but they haven't been smart or focused when it comes to causes," says iconic actress Shabana Azmi, who has spotlighted the plight of Mumbai's slum dwellers and done public-interest messages about AIDS. "Some of them do things quietly, but they say they don't want to openly attach themselves to a cause because it might be seen as going beyond their responsibility as entertainers."

"You worry that people will say, 'Your job is to give us three hours of escape from our lives, not to lecture us on how we should live,'" says Rishi Kapoor, romantic hero of the 1970s and '80s, and son of Raj Kapoor, the actor-director who made a string of films with powerful social themes in the black-and-white era. "It takes a genius like my father to find the balance between what people want to see and what you want to show them."

Reel Life

With Satyamev Jayate, Khan has torn up the unwritten compact between a star and his fans. The show makes no effort whatsoever to sugarcoat the message, and there's no concession to the audience's desires. You see what Khan wants you to see, and much of it is very, very unpleasant.

Each 90-minute episode tackles a single issue (...) with a brutal candor that has viewers squirming on their sofas. On a sparse stage before a small studio audience, the victims of India's social ills pour their heart out to Khan, who encourages them to relive their horrors. Their tales are interspersed with short field reports and discussions with experts on the scale of the problem. Khan supplies his audience with statistics compiled by a team of researchers. There's also usually an exploration of the laws pertaining to the issue and a can-do segment in which those who have overcome the predicament offer guidance to those still enduring it.

The format borrows from U.S. confessional shows, leading inevitably to comparisons to Oprah. But the similarity is superficial, at best. Unlike Oprah Winfrey, (...) Khan doesn't give his audience a break with digressions into health advice, cooking tips or celebrity interviews. The world of Satyamev Jayate is too full of serious troubles to allow for the respite of a low-fat cookie recipe. For the most part, too, Khan is careful to avoid easy scapegoating. When a woman shows pictures of her husband who, she alleges, bit off portions of her face because she "failed" to give him a son, the man's own face is pixelated out to hide his identity. Khan says this is not merely a precaution against legal action. "I'm not interested in individual villains," he says. "This is not a movie, so I don't need to show that so-and-so is a monster who gets his just desserts in the end. I'm interested in the larger issue: What is it about our society that makes a man think that a son is more important than a daughter?"

Collective responsibility is Khan's mantra. At some point in most episodes, the star looks straight at the camera, squares his jaws and delivers some variation of the theme that all Indians are at least culpable for the inequities in their society. He fixes me with that same look - stern but sincere - from his perch on the faded green armchair and launches into a soliloquy about responsibility: "The solution has to start with me, with every individual. After all, if these terrible things are happening in my society, then I have a share of the blame, because I've done nothing to stop them. A solution can only begin to appear once I accept it's partly my fault, and then you accept that it's partly your fault, and a third person [does that], and a fourth person." I come to understand why his critics say Khan's prescriptions are no more substantive than a fatherly lecture on morals.

While Satyamev Jayate is Khan's first foray into television, he dips into the Bollywood bag of tricks to keep his audience's attention. Each episode comes with large dollops of melodrama, the host employing the purple prose favored by Indian scriptwriters. Speaking of a whistle-blower allegedly murdered for exposing corruption in government road-building contracts, he intones in Hindi: "The torch of truth that he lit should never be allowed to wane in our hearts." When guests recount their personal tragedy, Khan's expressive face registers shock, horror and pain; he chokes up, and the camera repeatedly catches him wiping away tears. Every episode ends with a rousing call to action, usually in the form of song. "He has to use the language of Bollywood," says Anurag Kashyap, one of the hottest young directors in Hindi cinema. "If it were cut-and-dried, it would not be effective." Khan says his responses on the show are genuine, that he is not acting. But he admits to manipulating the emotions of his audience. "I'm not a journalist, I'm a storyteller," he says. "I can make you angry, sad, happy... That's my skill set."

The episode on domestic violence, for instance, features an all-male audience kept in the dark about the show's subject. Khan announces that they will discuss "the security of women in our society," and makes a maudlin appeal to the men as "protectors and defenders" of women. Khan then asks, "Where are women most unsafe?" It's a cue to a field report from a Mumbai hospital, where a doctor says six out of 10 women brought in for care are victims of violence at home. Now Khan unleashes a shocking statistic: 50% of Indian women have at some point been victims of domestic violence. The audience is on the ropes. "Here I had them preening as protectors of women," Khan tells me, his eyes lighting up as he recollects the men's reactions of shock and embarrassment. "Now they're suddenly confronted with the realization that, statistically, there's a chance that many of them sitting there have [been violent to women]. There's no getting away from it."

Leading from the Front

Khan's first ambitions in activism were humble: years ago, he toyed with the idea of making some public-service documentaries on road safety and etiquette. He dropped the idea as unworkable (a pity, most Indians would agree) but felt "like there was something I had to offer, somewhere down the line." That instinct is the product of nurture as much as nature. Khan's father Tahir Hussain, a moderately successful producer in the 1970s and '80s, made movies with social messages. (...)

But Khan's early career gave little inkling of a socially conscious streak. (...) He began to vary his roles with Lagaan in 2001. (...) Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, Lagaan was a spur for higher-quality work, including his 2007 directorial debut Taare Zameen Par (Stars on Earth), a critically acclaimed exploration of dyslexia, a condition the Indian school system barely recognizes. While 3 Idiots is principally a comedy, it too is a commentary on India's education system, taking aim at the tradition of rote learning, especially in universities.

Khan was finally ready with an idea for a TV show, but it would take him two years to develop Satyamev Jayate. (...) Though the show was bankrolled by Star India, the country's biggest cable network, owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corp., Khan agreed to do it only if it was simultaneously broadcast by the state-owned terrestrial station. His star power ensured that Star went along with other conditions too: the program, shot in Hindi, would have to be dubbed or subtitled in several Indian languages; there would also be tie-ins with radio shows and a weekly column in major newspapers. Khan says the full-court press is designed to "force you to pay attention to the issues we were covering, wherever you were in India."

He insisted the show air on Sunday mornings, at 11, traditionally a "dead" time for popular television. "I didn't want prime time," Khan says. "I wanted people to make an investment: you have to decide you want to watch." He calculated that as viewers sat to Sunday lunch with their families after the show, they would discuss what they had just seen. "It's not enough to shock and shake," he says. "It's important to start conversations." Khan also had conditions for the show's sponsors. Airtel, a cell-phone company, and Axis Bank agreed to be the conduits for any donations the audience would make to the causes being examined, and a major Indian charity agreed to match all the contributions.

Reality Check

The themes for the 13 episodes were chosen after weeks of brainstorming with a team of scouts, reporters and producers. Once shooting began, bringing Khan into contact with the victims of social problems the team had identified, it began to get very real. Listening to their stories was more emotionally exhausting than he had expected. "It left me very brittle," he says. "I'm not trained for this, to be sitting two feet from someone, having them pour their heart to you."

Even allowing for Khan's marketability, the show was not a sure thing. It was impossible to know if Indians would tune in on a Sunday morning to be hectored for 90 minutes on subjects they had previously preferred to sweep under the carpet. The decision to open the series on the subject of female feticide was risky too: the stories of women forced by their families to get rid of their unborn daughters were gut-wrenching. "We knew we had strong material, but we couldn't be sure how long people would watch before deciding they'd had enough of the horror and turn to a comedy or a cooking show," Khan says. Yet the first episode was watched by 90 million people.

The program's success has led, inevitably, to questions about a second season. Khan says he's interested, but wants first to take some time to assess the impact of the first series. It will be hard to top. There are tough subjects left to tackle, and they will likely offend more than a doctors' association. "How far does [Khan] want to go?" asks Kashyap, the director. "Will he tackle the taboos even Bollywood doesn't dare touch?" These, Kashyap says, include direct criticism of politicians or parties, discussion of sexuality and questioning the tenets of religion. Khan says he won't think about new themes just yet, but rules one out outright: "My interest is in the corruption in each of us, not just in politicians." Whatever Khan chooses to do next in his quest for grace, there's a good chance it will lift India a little closer to what he - and fellow Indians - would wish their country and society to be'.

Vedi anche:

- MasterChef India su Babel TV, 9 marzo 2013