Il numero di maggio 2022 della rivista digitale australiana Senses of Cinema include uno speciale dedicato al cinema popolare hindi, Welcome to Bollywood, con la seguente motivazione: 'This dossier is an attempt to complicate and diversify the monolithic concept of ‘Bollywood’, to break it out of its critical ghetto in Western film criticism and challenge the Eurocentrism of film studies that fails to recognise Bollywood as an artistic phenomenon'. Gli articoli sono decisamente interessanti. In testi diversi, riporto degli estratti, ma vi consiglio di leggere le versioni integrali.

MODI'S BOLLYWOOD: HOW 'SOCIAL MESSAGE' FILMS AMPLIFY THE INDIAN GOVERNMENT'S POLICIES, Uttaran Das Gupta:

'Released in March, 2022, The Kashmir Files claims to depict the plight of Kashmiri Hindus (commonly referred to as Kashmiri Pandits) who had to leave the troubled region in northern India in the early ’90s after being targeted by Pakistan-backed Muslim terrorists. While Kashmiri Pandit organisations and the Indian government claim that a few hundred were killed during the peak of the separatist movement, the film claims it was a genocide. Soon after its release, videos started circulating on social media of filmgoers calling for the ostracisation and killing of Muslims. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi encouraged constituents to watch the film, while several states ruled by his Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) gave The Kashmir Files tax waivers. Film critics have called out the virulent Islamophobia in the film. (...) There have been other intellectual interventions by journalists and scholars (...) exploring the relationship between the rise of ethnic majoritarianism in India and the billion-dollar Mumbai-based Hindi film industry, Bollywood. (...)

Genres of nation-building

One of the most significant trends in Bollywood since 2014 - when Modi was elected as prime minister - is the rise of certain genres, such as political biopics, sports films, historical dramas, war films, and social message films. None of these genres - except historical dramas - have received much journalistic or academic attention, possibly because it is often difficult to classify them neatly. (...) In this essay, I focus only on the social message films that promoted different policies of the Modi government. These films have received even less attention than the other genres, possibly because it is difficult to identify them as a genre in the first place. In fact, I have borrowed the term from an interview of Akshay Kumar, where he claims that this is his way of giving back to the country. While sports films, historical dramas, and biopics have a long tradition in Indian and international cinema, feature films promoting government policy are rare. (...) Also, these films might seem less harmful than obviously Islamophobic movies such as Padmaavat (Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 2018), Panipat: The Great Betrayal (Ashutosh Gowariker, 2019) or The Kashmir Files. This is perhaps another reason for the lack of research on these films.

However, as I shall show, the social message films surreptitiously purchase legitimacy for government and social policy, affecting millions of lives. I limit my study to the 2014-2019 period - Modi’s first term as India’s prime minister. (...) This was a period of immense socio-economic roiling in India, with backsliding democracy, a shrinking economy and ballooning unemployment. Acche din - or good days - as Modi had promised became increasingly elusive, but Modi’s own popularity remained undiminished as he continued to win election after election. In fact, the BJP won more seats (303 out of 545) in the 2019 elections to the Lok Sabha, the lower House of the Indian parliament, than in 2014 (282). How did Bollywood help? This is another question my essay addresses.

Towards a national cinema

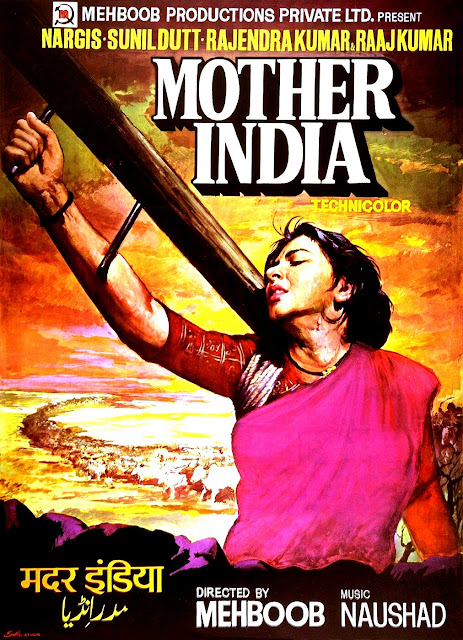

Before we analyse how India’s Hindu right wing is using popular Hindi cinema, it is important to chart a genealogy of films that have, directly or indirectly, served as vessels of official ideology since India’s independence in 1947. The importance of popular cinema as a medium of nation-building was recognised by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. (...) Several filmmakers - Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, B.R. Chopra - began making films that reflected, in the words of one critic, the “maudlin optimism of a new-found national independence and the social reflection of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s idea of state-led economic transformation and modernisation”. Some examples of Nehruvian cinema are Do Bigha Zameen (Bimal Roy, 1953), Shree 420 (Raj Kapoor, 1955), Naya Daur (B.R. Chopra, 1957), and Mother India (Mehboob Khan, 1957). (...)

It was also in the first decade after Independence that the Bombay-based Hindi film industry emerged as a pan-Indian cinema. (...) The optimism of independent India’s first decade would be dealt a shattering blow by the debacle in the border conflict with China in 1962. The humiliation of the Indian army was a personal defeat for Nehru as well. His daughter and India’s third prime minister, Indira Gandhi, would turn to cinema to resurrect her father’s image. During the Emergency (1975-77), a period of 21 months when Mrs. Gandhi would suspend democratic process, imprison opposition leaders, and rule by decree, she used a combination of censorship and patronage to control the film industry. Popular Hindi films such as Kala Patthar (Yash Chopra, 1979) advocated her policies such as the nationalisation of coal mines. (...)

Even Shyam Benegal - the leading director in India’s “new cinema” - would make films promoting government policy such as Manthan (1976) on milk cooperatives in the western state of Gujarat, Arohan (1982) on the land redistribution programme of a leftist government in the eastern state of West Bengal, Susman (1987) on handloom cooperatives, Yatra (1986) on Indian Railways, and the 53-episode TV series Bharat: Ek Khoj (1988), based on Nehru’s The Discovery of India (1946). Benegal’s 2010 film Well Done Abba (...) also promotes India’s Right to Information Act, 2005.

Modi’s socials

It might seem that there have only been a few films promoting government policy in the first five years of Modi’s tenure as India’s prime minister. However, when we think of all the other propaganda films - historical dramas, sports films, war films - along with these, we find that it is quite a significant number. Also, there are films, which I have not included in my list, that promote policies indirectly. For instance, Sooryavanshi (Rohit Shetty, 2021), a cop drama, engages with the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 - the Modi government’s contentious citizenship law - and India’s decision to abrogate the special status previously given to Kashmir without directly referring to it. Similarly, Toilet: A Love Story supports Modi’s decision to demonetise high-value currency notes in 2016, which several economists claim led to widespread job loss and slowed down the country’s economy, with a throw-away dialogue.

From our list, it is not difficult to prove that the first two are, in fact, propaganda films, despite Akshay Kumar, the leading actor of Toilet: A Love Story, claiming it isn’t one. Their producer, the short-lived production house KriArj Entertainment, released several films with social messages between 2016 and 2018 before shutting down because of financial problems. Besides the two films listed above, these included Pad Man (R. Balki, 2018), a biopic of social entrepreneur Arunachalam Muruganantham who made low-cost sanitary pads widely available, and Parmanu: The Story of Pokhran (Abhishek Sharma, 2018), a period drama on India’s 1998 nuclear tests when a BJP government was in power in New Delhi'.

'English in “Bollywood masala” films

There has been a gradual increase in the amount of English used in Bollywood Masala films since the ‘70s, but even today, it consists of English words inserted into Hindi sentences; and formulaic phrases in English which are relatively easy to understand. This is the case even when the protagonists are elite urban Indians whose real-life counterparts would use English a large proportion of the time. A good example is Jab We Met (Imtiaz Ali, 2007) where the heroine Geet (a young Punjabi woman from an English “convent” school in Mumbai) says to Aditya (heir to a Mumbai-based business empire) on their unplanned road trip:

Tumne pehle kabhi aise lake mein jump kiya hai? ‘Have you ever jumped into a lake like this?’ (...) Aditya responds with a couple of recognisable formulaic English phrases: Arey Geet relax, arey listen to me. ‘Hey Geet, relax, hey listen to me’.

This pattern can be found even in Bollywood movies known for breaking the masala mode such as Dil Chahta Hai (Farhan Akhtar, 2001). The intense code-switching on a Hindi base (often referred to as “Hinglish”) is symbolic of modern urban English-medium educated elites, who are very seldom shown speaking English in isolation (possibly some business settings) or Hindi in isolation (possibly to older relatives). It is relatively easy to follow for Hindi-dominant audiences with low English proficiency. This is of course the opposite of the English sentences with Hindi inserted words used in diaspora films such as Monsoon Wedding (Mira Nair, 2001) and Bride and Prejudice (Gurinder Chadha, 2004). In reality, urban Indian English medium educated elites have been shown to have Hindi loss and in some families with high mobility and parents from different language backgrounds, English monolingualism is becoming more common.

Descriptions of (...) “Indian English” outside of films

The scholarship of Indian English (...) was motivated by resistance to an imposed British English standard in Indian education. (...) “Educated” speakers of English as an additional language had produced a variety of English with stabilised indigenous features which could act as a local standard. These features may have their origins in language transfer but should not be considered learner errors. This national variety, “Indian English”, was a challenge to support empirically, given the extreme variation it implies in proficiency, language background and urbanisation. The Indian English accent is considered to have some general non-regional features such as a single vowels or monophthongs in words like know, and a sound more like a ‘v’ in words beginning with /w/. As far as grammar is concerned, even highly proficient speakers demonstrate features like the deletion of definite and indefinite articles, over-generalisation of the progressive form of the verb, lack of subject-verb inversion in questions, changing there is at the beginning of a sentence to is there at the end of a sentence. Less grammatical and more conversational features such as only with an emphatic meaning, tag questions at the end of sentences such as is it, isn’t it, no/na, have also been shown to be characteristic of Indian English. (...)

Representations of Christians in Bollywood movies

Christian characters are always shown as Catholic with western names, even though in reality they may speak an Indian regional language and have a name associated with that language. If they are from Goa, they have Portuguese surnames. Christians are often conflated with Anglo-Indians (a non-regional, typically Christian ethnic minority based on British ancestry). (...) Finding Fanny is exceptional in that all the main characters are Goan Christians. (...) Below I set out a few scenarios (...) which could explain why such a wide range of features is on display in the speech of English dominant Christians from Bandra:

1. The syntactic features attested for Indian English, in addition to or what and no, are in fact exclusively features of English dominant/English only Christians, and do not occur in the speech of speakers of English as a second/additional language.

2. Second/additional language speakers of English have developed grammatical features in parallel with Christians (and Anglo Indians) who shifted to English more than a century ago, because ultimately all features are due to transfer from the underlying languages.

3. Christians, like Anglo-Indians, have had to “Indianize” over time, and so in addition to the original features of their English they have acquired some of the more stable Indian English features.

4. All the features, those noted for second/additional language speakers and those noted for English-dominant Christians, are Mumbai (or even just urban) features. The use of men/man at the end of sentences (it’s 8 o'clock in the morning man) is associated with Mumbai specifically. (...)

I don’t offer these scenarios because we should choose one that is correct. They all have some element of truth to them, and they all offer clues to the puzzle. (...) Urban Indian English is not often on display in Bollywood masala movies. Partly this is because the movies are in Hindi, but it is also because the protagonists are often so elite that their status would be lowered by some use of these features (their intense Hindi-based code-switching is not low status). Certain features such as the lack of subject-verb inversion in questions have been associated with the lower middle class. (...) Bollywood masala films have incentives to stereotype Christians, and to stereotype their English, as a distinctive dialect. However, the features they use to do this can be found in other varieties of Indian English. On the other hand, scholars of “Indian English” have incentives to reify a national standardised second language variety common to all speakers of English in India'.

Vedi anche:

- Welcome to Bollywood: Critica internazionale e Nazionalismo. Il testo raccoglie i link a tutti gli articoli della serie.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento